If you’ve ever taken a statistics course, you’ve probably heard an instructor warn that “correlation does not imply causation”. After hearing it, I definitely knew to be wary of making such associations, but never had a good answer to the question: “If there are no causal relationships at play, why am I seeing correlations?”

In this post, I’m going to talk about three ways in which you could find correlations between two variables even though there’s in fact no causal relation between them. Though my examples are completely made up, I’ll illustrate the following:

- Why countries introduced to social media might see rises in extremism,

- Why we might find that people who are vaccinated are more likely to be diagnosed with autism, and,

- Why an amateur dietician might come to the conclusion that weight gain is an appropriate remedy for bad skin.

First, let’s define correlation and causation a bit better.

Let’s start with correlation. If I randomly picked a person from the population, and found out that they had a college degree, I’d find that they were more likely than the average person to own a Tesla. This means that a person’s having a college degree is correlated with them owning a Tesla, i.e. knowing if they have a college degree changes the likelihood that they also own a Tesla.

Now does this mean that having a college degree causes them to own a Tesla? Perhaps, but not necessarily. If I randomly picked a person from the population, and put them through college to the point where they got a college degree, and then found that they became more likely to own a Tesla, this would be an instance of causation. More precisely, if having some property A (like a college degree), causes you to have some property B (like owning a Tesla), then forcing someone to have A will make them more likely to have B.

From now on, I’m going to refer to these properties (e.g. having a college degree, owning a Tesla, etc.) as variables, because they can take on one of many values (e.g. True or False). When talking about causal relationships between variables, it’s convenient to use a Causal Diagram.

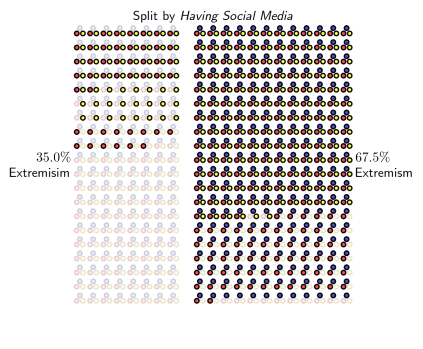

In the diagram above, we’ve represented a situation in which A causes B. If there were no arrow, we would represent a situation in which A does not cause B, i.e., even if we had forced A to be true, it would have no influence on whether B were true.

I’m now going to describe three ways in which, despite there being no causal relationship between two variables, we still observe correlations between them. Before we jump in, let me remind you again that all these examples are completely made up for the sake of illustration.

The Mediator

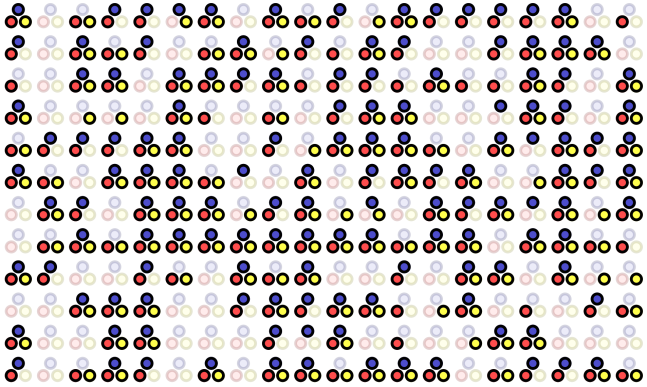

I’m going to start off with the most intuitive but least surprising way in which two variables could be correlated despite having no direct causal relationship between them. Let’s say that we’re looking into whether we can blame social media for a rise in extremism. Consider the Causal Diagram below:

Here, we’re assuming that social media doesn’t directly cause a rise in extremism in a country, but rather causes the country to have a platform for Fake News, and that this platform in turn causes a rise in extremism. Let’s put some numbers on things. Let’s say 60% of all countries have widespread use of social media. Since certain social media companies don’t do a great job of filtering out Fake News, let’s say:

- If social media has widespread use in a country, there’s a 95% chance it has a platform for Fake News, and,

- If social media doesn’t have widespread use in a country, there’s a 30% chance it has a platform for Fake News (perhaps a messaging app or some other medium).

Furthermore, let’s say:

- If a country has a platform for Fake News, there’s a 70% chance it experiences a rise in extremism, and,

- If a country doesn’t have a platform for Fake News, there’s a 20% it experiences a rise in extremism.

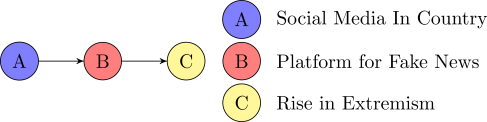

Lets look at an imaginary world of 400 countries at a glance:

In the picture above, each triplet of dots is a country. If the dot is shaded dark, then that variable is true for that country. For example, if a red circle is shaded dark, then that country has a platform for Fake News.

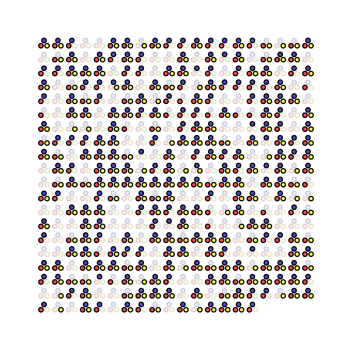

What we’re interested in seeing is whether countries with widespread use of social media (blue dots) are more likely to see a rise in extremism (yellow dots). We study this by splitting the population by whether they have widespread use of social media:

In the left column, we’ve grouped countries that don’t have widespread use of social media, and in the right column, we’ve grouped countries that do. It’s easy to see from this grouping the effect we suspected, only 35% of countries without social media have seen a rise in extremism, while 67.5% of countries with social media have seen it.

This clearly suggests that if a country wanted to curb the rise in extremism, they should ban social media, right? Well, sort of. What they would be missing is that widespread use of social media caused a rise in extremism only because it created a platform for Fake News. You can see this more clearly in the picture below, where we first split the population by whether or not they have a platform for Fake News, and then see if countries with social media have any influence on the rise in extremism for each group separately:

What we see is that the effect almost completely disappears, and any residual effect is only due to the fact that I’m using a population of only 400 countries as opposed to larger number.

So would you have been wrong in saying social media causes a rise in extremism? No, because in this case, social media is an indirect cause. But understanding the mediator leads to the insight that if you want to control the rise in extremism, you’re better off preventing social media platforms from becoming platforms for Fake News, than banning them altogether.

So what’s the takeaway? If you’re pretty confident that one variable causes another, consider whether that causation acts through a mediator. Controlling the mediator would be a more effective way of controlling the variable downstream.

The Confounder

In the case of the mediator, you’d still be right in technically saying that A caused C, even if it caused it indirectly. We’re now going to look at the most common source of spurious correlation, the confounder, a.k.a. the ‘common cause’. Here, you would not be correct in assuming the correlation you’re observing indicates causation.

We’re going to see why we might find that people who are vaccinated are more likely to be diagnosed with autism, despite there being no actual causal relationship between them. Let’s say we have population of a million people. Of these million people, 30% of them happen to be children. Since its more common for a person to get vaccines around when they’re children, lets say that:

- If you’re a child, there is a 70% chance you got vaccinated in the last 6 months.

- If you aren’t a child, there is a 10% chance you got vaccinated in the last 6 months.

Now, since its more common for someone to be diagnosed with autism when they’re a child rather than when they aren’t, lets say that:

- If you’re a child, there is a 15% chance that you get diagnosed with autism.

- If you aren’t a child, there is a 2% chance that you get diagnosed with autism.

The causal diagram above reflects these relationships, but notice that it doesn’t explicitly reflect any causal relationship between being recently vaccinated and having autism. Nevertheless, if one were to just look at these two variables, you’d find that people who had just been vaccinated were almost four times more likely to be diagnosed with autism that those who hadn’t!

Heres why. The picture below on the left represents the population, where each triplet of dots is a person. As before, if the dot is shaded dark, then that variable is true for that person.

Let’s rearrange the population a bit in the picture below, separating people who haven’t been vaccinated (on the left) and those who have (on the right).

The astute anti-vaxxer might look at the number of people diagnosed with autism in each group. On the left, you’d see that only 3.5% of people are diagnosed with autism, while on the right, 12.5% of people are. This might lead a person to the conclusion that getting a vaccine makes you almost four times as likely to be diagnosed with autism! Note that this is despite the fact that in the Causal Diagram I used to generate this population, there is no actual causal relationship between vaccines and autism.

So what would an epidemiologist do in this situation? Assuming they suspected that being a child is a confounding variable, i.e. a likely cause of both getting vaccinated and being diagnosed with autism, they would control for whether the person is a child. In the picture below, we see how this is done.

We first split our population based on whether the person is a child (on the right) or not (on the left). Then, we ask separately for each population: does having been vaccinated make you more likely to have autism? Looking at the numbers, you’d see that people are no longer four times more likely to be diagnosed with autism if they’d been recently vaccinated. As it turns out, the only reason you see any difference at all is because I’m representing a million people with 400 people.

So what’s the takeaway? If you see a statistic saying “people who do A are X times more likely to have condition B”, think about whether there might be a common cause responsible for that correlation.

The Collider

Next up, what I think is the most interesting but least obvious source of spurious correlation: the collider. Let’s imagine an amateur dietician who has seen about 200 clients. In the population, let’s say:

- 40% of people are overweight, and,

- Independently, 40% of people have acne.

Now let’s assume that both being overweight and having acne might be reasons a person would see a dietician. Specifically, let’s say:

- If a person is not overweight and doesn’t have acne, there’s a 10% chance they’d see the dietician,

- If a person is either overweight or has acne, but not both, there’s a 60% chance they’d see the dietician, and,

- If a person is both overweight and has acne, there’s a 70% chance they’d see the dietician.

Now lets say we look at the population as a whole, as in the picture below:

And now, as before, we check if being overweight makes you any more or less likely to have acne by splitting the population into those who are overweight, and those who aren’t:

As expected, we see that being overweight has no effect on having acne, i.e. a person’s chances of having acne are the same (40%) whether or not they are overweight.

But, let’s now imagine that the dietician made the mistake of assuming that their clients were representative of the population, i.e., they assume that trends they observe amongst their clients are trends present in the population. The figure below illustrates this. The right column is the subset of the population that has visited the dietician. On the top of the column, we have the people that are overweight, and at the bottom are the people that aren’t.

What would be apparent to the dietician is that, of their clients, those who are overweight are only half as likely to have acne. This might make them want to draw the conclusion that weight gain is a good remedy for acne. As we saw in the earlier figure, this conclusion would be wrong! In the population as a whole, having acne and being overweight were independent.

Is this something only a dietician should worry about? Well, it comes up more often than you might think. Imagine that you leave a sheltered childhood to join a big university. You might notice people who are intelligent are less likely to be athletic. Though, since being intelligent and being athletic are both sufficient causes for getting into the university, you might be incorrect in generalizing this observation to the population at large.

So what’s the takeaway? If you’re making observations about a subset of people, be careful about whether the variables you’re observing caused them to be in subset. Scientists studying psychedelics in the 60’s had a particularly hard time with this because the people who signed up to participate in their studies did so because they were inclined to try psychedelics and, and so were not very representative of the population at large.

Summary

I showed three ways in which you could observe a correlation between two variables (say, A and B) even though one didn’t directly cause the other. In the case of the mediator and confounder, we saw that there might be a third variable you’re missing, and had you controlled for that variable C, the correlation you see between A and B would disappear. However, in the case of a collider, controlling for that third variable C is the source of the correlation, so you want to make sure you’re not controlling for it. We saw that people tend to introduce correlations through colliders by unintentionally assuming a subset of the population is representative of the whole, thereby unintentionally controlling for a variable.

The next time you come across a statistical correlation used to argue for some causal relationship or another, I hope you use these lenses to consider ways in which that correlation might be spurious, and what else you might need to know to see if it is.

References

Want to know more about probabilistic modeling and causality? Check out the resources below:

-

The Book of Why: The New Science of Cause and Effect by Judea Pearl (2018), which is a great popsci read and what inspired me to write this post,

- Chapter 2 of Decision Making Under Uncertainty by Mykel J. Kochenderfer (2015), which is a fantastic textbook written by my PhD advisor at Stanford, and,

- This Coursera course on Probabilistic Graphical Models, if you want to know how to use this stuff at scale.